Mohamed Gibril Sesay

The contest for the APC’s 2028 flagbearer has begun long before any official declaration. It began through posture, movement, style, and the subtle work of positioning. What we are witnessing goes beyond being simply a competition of individuals. It is a clash of political types; it is about different ways of getting traction.

I see seven broad categories and tendencies shaping this contest: the English-English Speakers, the Party Machine People, the Populists, the South-East Contenders, the People with Bases, People who had contested before and those clearly or in disguise talking about being endorsed by EBK. Some aspirants belong to more categories, but often, one or two dominate their efforts, and do the heaviest political work. That dominant trait becomes how the party and others read the flagbearer, evaluate them, and sort them out.

Let’s now talk more about each of these tendencies and groups

The English-English Speakers and Verb Agreement Crowd (VAC)

This group of flag-bearer aspirant arrives fully dressed in grammar. Their sentences land correctly. Subject agrees with verb. CVs read like UN bios. Degrees sit neatly in chronological order.

I like them. I speak-speak English too.

But here is the small problem: you don’t speak English in a cookery shop. You don’t display your certificates at a junction like posters. This reminds me of a late friend’s relative. Master’s holder. Big academic thing in our teenage days. He hung his Master’s certificate bigly on the wall of his parlour. Anytime we were playing the type of football called Guinea Goal, teasing ourselves, or just being teenagers, he would point at the certificate and shout: “Look at this! Look at this! You unserious boys! If only you look at this certificate, you will become serious!”

Ayyybo. Not that the certificate was not respected. Many of us who would become members of the Verb Agreement Crowd sort of did. But in the junction and the street, we preferred the people we shared roasted cassava with, or bread and kanda. The ones who spoke our slang. Not the man pointing at certificates.

That tension is exactly what plays out in party politics.

Politics in the APC is not a seminar or a courtroom, or a speak-speak business. The English speaker, often cheered on by the Verb Agreement Crowd, tends to confuse clarity of expression with clarity of connection.

Let me make some distinction here. The Verb Agreement Crowd are not necessarily candidates themselves. They are the grammar audience: the book man dem and book ooman dem who listen for syntax before they listen for substance. They evaluate politics the way WAEC marks English – ticking correct tense, nodding at polished delivery, rewarding elegance of speech as though it were evidence of political depth. Many are fluent in what tar-gron people call English-English: the language of radio panels, hotel workshops, donor-funded PowerPoint slides. They know how to line up fashionable buzzwords: youth empowerment, gender equity, national cohesion, sustainable development. Ten to fifteen of these can be strung together beautifully, and book man dem and book ooman dem nod their heads in admiration. Perhaps you remember those men from our younger junction days – the ones who had lifted a few Bob Marley lines into their heads. They would seize our attention, shouting: “No woman no cry! There is ‘War in the east, war in the south!’ ‘Fire!’ For this is ‘Pimpers Paradise! Redemption Song!’ Don’t treat me ‘like puppet on a string! Emancipate yourself from mental slavery!” And we would hang our mouths in admiration. But when you listened closely, it was mostly incoherent mouthing, a joblo-jabla of barely understood phrases.

That is exactly the kind of performance we hear today from many in the Verb Agreement Crowd. Strings of high-sounding expressions, delivered with confidence but thin on meaning. Even when they talk to very ordinary people in Krio, you would see their expressions sweating under the weight of what some musician call ‘big big English way day make we languish’. Or worse still, when they enter that affected mode – mesef day speak speak big English o, hehehe – of what people call “Bob Marley explanation without the lyrics.”

Often, the Verb Agreement Crowd are involved in a delusional moral hierarchy or framing. Those who cannot properly “lollipop” their buzz words are often looked down on. A slip in grammar becomes a slip in credibility. Politics turns into an oral examination, with marks awarded for pronunciation and accent, and those heavily influenced by their L1 (or as we say, those with Themne, Mende, Limba, Loko in their teeth when they speak the acrolect English or Krio) are given low grades in the political calculations of the Verb Agreement Crowd. Aaaaa. So you see eh, I can speak-speak like the Verb Agreement Crowd; they are a company I also keep – That’s why you see this Crojimmy man seeking to impress by using the word acrolect above, which simply means a language or accent that is considered better than others.

Come on, don’t get me wrong, I know many in the Verb Agreement Crowd mean well. But they are small in number, thin in structure, and the overwhelming number are largely disconnected from the ground game of party politics.

The English speaker as flagbearer aspirant belongs to the same ecosystem as this crowd. They are part of one another’s audience. They praise each other’s interviews. They circulate each other’s articles. They dissect grammar on radio panels. They reinforce each other’s confidence. It becomes an echo chamber of correctness. And because that echo feels affirming, the English speaker invests disproportionate energy in refining interviews, crafting Facebook posts, and polishing arguments, when he should be building presence, relationships, and memory in the party’s bloodstream.

The challenge here is practical, not intellectual. The Verb Agreement Crowd does not do ward work. They do not mobilise delegates. Most do not attend pull na doe, funerals, or commemorations of party members in constituencies. Busy professionals. Diaspora lives. Little patience for the slow, unglamorous labour of party cultivation.

Yet this is often where the English speaker concentrates his political labour – inside grammar-friendly spaces – mistaking intellectual validation for political traction. The applause of the Verb Agreement Crowd sounds loud, but it rarely converts into delegates, ward loyalty, or votes. But oh, the delusion persists, the English speaker mistakes the support given to them by the verb agreement crowd as the support the country or ordinary people are giving them. They forget that it takes a lot more.

The problem, therefore, may not be about being unfit for the presidency they ultimately seek. Many of the English speakers are capable, experienced, thoughtful, and individually better than the caboodle currently mis-governing the state. The problem is translation during their campaigns. Grammar begins to substitute for political work. Fluency becomes mistaken for connection. Correct sentences begin to feel like evidence of readiness.

But hmmmm, when push comes to shove, in the chase for the foremost flagbearer poda poda, nor to so e kin be o. You don’t practice poda-poda run-run by perfecting your use of Uber Apps. That is mis-location. Because, hey in this Flagbearer race you now have to speak to rooms that are not listening for grammar. And you don’t’ shout ‘commodification’, or ‘jurisprudentiality’ or ‘legitimation’ in a market that runs on familiarity, loyalty, memory, and reciprocity. You cannot ‘big-word’ or ‘verb-agree’ your way into a delegate conference.

In a cookery shop nobody asks for sustainable nutritional frameworks. They ask if the soup is ready and whether you know them. Pointing at blown up posters of certificates is baldhead in a bola-bola junction, and relying on the applause of the Verb Agreement Crowd is self imposed limitation.

I have what I would call an “outside politics” relationship with many of the English speakers. One has been a friend for decades. We sabi provoke wesef. He is a man who likes to achieve and to be seen as achieving, and he would be an achieving president. Another has been an intellectual partner in the last few years, a solid younger chap with serious mental discipline. He will bring that to the presidency. Another is like a little brother, his home place is Fourah Bay where I grew up. And he’s great chap, with passion and energy. And God knows, our presidency needs that. A few of them we crossed paths with at university. One, from a minority ethnicity, is a data man, a strategic thinker, with a coherent governance programme he feels deeply passionate about. This country needs that type of president. There is also a lawyer and investment banker, from a family of siblings we have long respected. And there is my isten Krio man too, a solid intellectual without the arrogance that such achievement brings. We have shared personal moments, intellectual exchanges, home visits, laughter, and long conversations.

We have also talked seriously, many times. About politics. I have told them to play to their strengths, not to borrowed styles. To gather the language of politics from the ground, not from dictionaries, theories, or hotel seminars. To connect their bios to common speech, to their own connections with people and with the party. To be visible. To show up. To speak with conviction. And most importantly, when they talk about the caboodle ruining (sorry, running) the country, to do so with clarity and courage, not with timid politeness. Politics rewards those who sound like they believe themselves. It rarely rewards those who are merely well spoken. Next, let’s talk about the Party Machine People

- The Party Machine People

These ones don’t impress you at first glance. They don’t sparkle on paper. But they know where the paper is kept. They understand the party. They know who was offended in 2005 and never forgot. They know which apology was accepted publicly and rejected privately. They know who controls which district executive, and who only pretends to.

I see two people as mainly representative of this, one a former parliamentary leader and the other a former youth leader. They are not very loud. Nope. No. Rather, it is because they are legible to the system. They speak the party’s memory fluently. The party workers, the bolt and knot people who do the arduous tasks of going to the party offices recognizes them; those who hold party positions at ward, constituency, regional and special organs like the veterans, women and young congress, and those who are often called the ‘old wan dem’ know them by name, by face and by the party work they have done together. That recognition is a key asset.

Now, the party machine people know that politics is less about speeches or grammar or even daily drama or turning to everyone who says ‘bra, we day for you’. That would be the political equivalent of listening to every voice in the market. They know politics speaks less in speeches in more in sequencing. Often, they avoid speaking in the ‘English spaces.’ They concentrate on party spaces, and are very fluent in the party linguistic registers or how to talk like an APC person in an APC gathering. They know who you greet first. Who you sit next to. Who you don’t mention.

This is what is called tacit knowledge. It is a key asset. It is about what actually wins internal elections. They know the boots and laces of the party; where things tighten, where they loosen, and where they must never be pulled.

They know the different types of players.

They know whose word is solid, and whose word needs reinforcement through an extra network, and exactly which network that should be. They know who influences who, and who only looks influential. They know those who prefer others, but don’t mind them, and how to sit comfortably in that grey zone. Crucially, they know the kondo you don’t waste powder on. And those you must never ignore.

They know who to meet, at what moment, and for what purpose. Some people you meet early. Some you meet late. Some you only meet when the numbers are almost settled. They understand timing as strategy.

They also read noise very well. They can tell the difference between people whose words matter on their own, and those whose words only mean something when added to a trend. They spot the ones full of sound and fury, signifying very little support. These ones don’t confuse volume for value.

This group rarely excites the crowd. But it calms the room where decisions are made. At this moment, they don’t chase ‘general elections’ popularity at this moment. What they do is chase and accumulate actual votes within the party. By the time others are making arguments, they are already counting.

Thus, where the English speakers trust grammar, the party people trust memory. They have built reciprocity or ‘tinap for me ar tinap for me’ over time. Nor to theory o, but actual favours. They helped people when it mattered. They opened doors, fixed problems, created opportunities, and remembered who benefited. In party politics, this kind of help sits quietly and waits.

If English speakers sometimes talk past the party, the party people speak within it. And they do it in highly sensible ways that we must not tehkeh. This brings me to a discussion of different kinds of sense in political life. At least three matter here: book sense, common sense, and party sense.

Book sense is the language of theory, concepts, grammar, and credentials. Common sense is the language of lived experience, what people know from daily life, struggle, survival, and observation. Party sense is different again. It is the instinct for timing, loyalty, reciprocity, silence, presence, and internal arithmetic. It is knowing not only what to say, but when to say it, to whom, and who must never hear it.

Some people are very good at translating their book sense into common sense. They can explain complex ideas in ways ordinary people understand. Others are good at translating their common sense into book sense. They can observe politics deeply, and then theorise it convincingly. But the real power in internal party struggles often lies with those who can translate book sense, but more so common sense into party sense. These are the ones who understand mood, memory, offence, loyalty, obligation, and opportunity. They read the room before the room speaks. They sense shifts before they become visible. They carry the real conversations long before microphones appear. Don’t tehkeh them.

Next, we turn to the populists

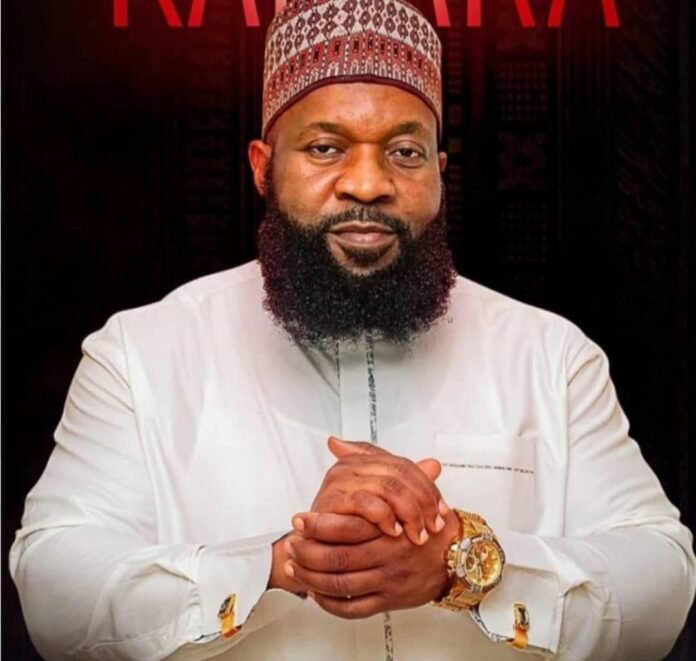

- The Emerging Populists – the Jagaban/Ormodu Type

This is almost a category of its own. The populist. A foremost example is Jagaban. It is not only about the money, it is also about the way he talks. He speaks like an isten man with money who talks his cash loud and clear at the junction. He dresses like it too. But in a way that shows his Muslim leanings, like a mosque chairman who can also hold his own in the expressions and registers of the dove-cut market argument. Backed by resources, generosity, and a certain muscular confidence, the kind of confidence you find in a man who has settled his own problems and now believes he can settle everybody else’s. His logic sounds confusing to English speakers because it is not trying to convince them. He speaks in the short term of common sense that is the way many ordinary people speak or make sense of things. Ferry nor day? Bo look me day go China right now for go arrange for buy them. He speaks of relief as coming now. He reduces governance to “I will handle it. now” And people believe him, because in everyday life, that is often how things actually get handled. When people are hungry, you don’t say I am gathering money to give someone to go get cooking things at the market. You say ‘look, den day pan pull eat’.

He speaks directly to failure and neglect. Not abstract failure. Not policy failure. Not, hmmmm, wait let me find a big English words from my ‘Longer Oxford Diction. Okay I found it. He does not speak such words as hyperbureacratic failure’ or ‘technocratically induced failure’. He speaks in plain terms about physical neglect. The rotten ferry that didn’t come. The long queues and frustrations about transportation at PZ, Shell, Calaba Tong and costs of travelling from and to Bo, Kenema, Makeni, Port Loko, Blama and Falaba.

There are two kinds of neglect he exploits very well. First, public service neglect of ferries, buses, infrastructure, basic movement. Things people experience daily. Second, patron service neglect – not being serviced, not being remembered, not being supported as a group or a place.

His response to both is practical and visible. He provides. He shows up. His residences become places of real bra tin dem: cooking every day, people passing through, people eating, people feeling seen. Like that one he has at Malta Street, just over the street from Crojimmy where I grew up. My Crojimmy, Kossoh Tong, Fourah Bay relatives and friends tell me of the daily awujor that goes on there. They speak of him as their area man, since when he came down from Blama to attend school he lived in that area. He donates here and there, often, just loudly and consistently enough to be noticed.

The masses like this. And that gives him an advantage.

But populism attracts attention. And attention attracts appetite.

Now you see some elites circling, like yiba, if we are being honest, wanting a cut. Some want a share of his stage. Others want access to his money. Are they committed to him? Hard to say. But they are committed to the opportunity he represents.

He enjoys the attention. Who wouldn’t? And in enjoying it, he begins to shift gears.

You see it in some of his emerging discourse. Praising Bio. Softening his edge. Thinking that a little something to some first lady initiative might buy him space, or slack, or even strategic favour. Many people make this mistake: believing that being a “preferred” APC candidate in SLPP eyes gives them an advantage

It doesn’t.

The SLPP wants the SLPP to win. Not a Jagaban. Not an English speaker. Not a party man. Anybody thinking otherwise is confusing strategic accommodation with political love. Or you may think about how smooth talking rapists groom victims. And the SLPP, as the de-facto governing party will seek to put ‘san-san’ in the garri of the APC flagbearer race, in hopes that may make it uneatable during the 2028 elections.

Meanwhile, Jagaban is silently derided by many English speakers. And especially their Verb Agreement Crowd. They tehkeh him. They think grammar is a substitute for brilliance, and English is evidence of fitness to rule. They laugh at his style, his confidence, his simplicity.

This is the irony.

Many of those Verb Agreement can speak good English but struggle to put down coherent ideas. But many of the things they say, if translated into Krio or any indigenous language, would sound utterly mundane, non-starters, empty calories, sometimes utter nonsense

Jagaban’s ideas are not said with the big-big speak-speak English-English words like sustainability, GDP to tax ratio, legal framework. But Jagaban’s ideas land. They speak to neglect people feel, not neglect they analyze. That is his strength. And also his greatest challenge.

Populists rise fast. Reminds of people who throw money in the air in poor places, and do it consistently. People rush to catch the money. Throw-up-in-the-air generosity attracts crowds. And crowds attract appetite.

Soon, groups from all over begin to swarm in, sensing a generous feast. Everybody shows up. Everybody claims closeness. Everybody wants something. The problem is that generalist benevolence weakens loyalty of the particular. If you can give to every Jack and Jill, or Sallay and Sullay, a person needs not be particularly loyal to you, and in an intra-party contest, it is the particular that counts.

The general population, often neglected after electoral moments milks their chances during these moments. Many do not expect such personalized benevolence after the electoral moment, so now that it has come, they are all over chasing it. But again, an overwhelming number of these are not active party people; they cannot formally vote in party internal elections. The active party person – the ones who actually become delegates may also do this milking of the moment. And that’s exactly the point, many know this is a ‘eat-eat’ moment’ but also as party people they know the flagbearer awujor is not something that sustains them after the race. What sustain them are those other long term relationships with patrons who had been with them in small-small invisible way over a long period. Politics for the active party worker runs on expectations of continual benefit, not the very time-bound electoral generosity. Which is why commitment to persons with money is often thin. They could change even in the very hall where the flagbearer election is held.

Worse, generosity can begin to look like purchase to the man doing it. And once you feel you are buying people, if God nor help you, respect for them quietly drains away. And with that comes talk that belittle the party worker, or delegate, or big wan dem, and these contemptuous talk undo the gains.

Jagaban is rising. But unless populists convert generosity into structure and appetite into loyalty, the noise around them will eventually exceed the numbers beneath them. Jagaban attracts interests quickly. If he doesn’t learn to separate genuine support from opportunistic proximity, he may find that by the time the real counting begins, the noise around him is louder than the numbers behind him. But the English speakers ‘tehkeh’ him. And I mean here, the more general intellectual sort, not only the candidates. Or they deride his money throwing, though many are now moving to ring-fence his generosity, their own form of ‘elite capture’.

- The South-East Contenders

Lots of people tend to tehkeh flagbearers from the South East, forgetting that APCs foremost politician, Siaka Stevens, despite efforts to trace ethnicity elsewhere was a man from the South East. Truth be told, it is easier to be APC in the North and West than it is in the South and large parts of the East. That is the moral strength: sacrifice, loyalty. Their weakness, unlike Stevens is inability to penetrate the North and West with the sleight of political alliances that could make them top contenders.

And, hmmmm around some South-Eastern contenders, a quiet question follows them everywhere: Are they really running to win, or positioning for something else? Auditioning for relevance. Testing the waters. Keeping a seat warm. In party politics, uncertainty is corrosive. Delegates do not invest in ambiguity. And their doubts settle, they hedge. They listen politely, attend meetings, but place their real bets elsewhere.

It is however, a little different for the most famous contender from the South East: Sam Sumana, the former Vice President. Everyone knows he is not in it for show. He is in it for it. He has shown staying power. He has endured. He has remained. His claim is grounded in experience, memory, and survival. Yet even here, the ground might have shifted.

For long there’s huge uncertainty about his candidacy – legal, procedural, temporal, political. That uncertainty explains, more than anything else, why some early supporters drifted toward contenders whose eligibility appeared less complicated. In politics, loyalty often bends toward certainty. The drift away from him was often quiet. A meeting missed. A call not returned. An involuntary sigh that escapes the mouth when the name is mentioned: bo yorba. Even as clarity has improved, the field has not fully returned. Politics, like social life, does not forgive indecision easily. The critical question now is whether he can pull some of these back. Some of these people are so far in the potor-potor of other campaigns that moving back is as hard and may be harder, than just continuing with those they have pitched tents with.

And there’s another harder truth: sympathy is not the same as desire. Many support the that Sam Sumana should be allowed to contest. That the past should not disqualify him. But wanting someone to run is not the same as wanting them to win. The step from moral support to electoral commitment is a big one.

Beyond this, Sumana faces a subtler challenge: perception. There is a lingering belief among some party actors that he carries political grudges against key figures within the party, and that, if he clinches the flagbearership, he might act on them. Whether fair or not, this perception shapes behaviour. Key figures and others ask quietly: Is this a big-tent project, or a settling-of-scores moment?

This is not just about the candidate. It extends to his inner circle. Are the key supporters expansive or exclusive? Forgiving or foreboding?

To be clear, Sam Sumana knows the game. He was Vice President. He understands power, institutions, and political timing. No one should tehkeh him. Generally, no one should tekheh flagbearer candidates from the South East , or the preferences of party activist therein. This is a questions of arithmetic. And the arithmetic matters. The South-East holds a significant bloc of delegates. In a tight contest, every vote counts. This makes the region indispensable, even if no South-Eastern candidate wins outright. Kingmakers emerge where winners do not. They complicate the field. They force conversations others would prefer to postpone. And in tight races, they become kingmakers or spoilers.

- The People With Bases (Geography, Ethnicity, Networks, and Money)

There is another category quietly shaping this contest: the people with bases. Not vibes. Not slogans. Bases. Some have geographical bases. A district where their name carries weight. A chiefdom where people feel they “own” them. A hometown where their presence automatically generates delegates, mobilisation, and defence. Many contenders struggle here. You often see them trying to manufacture connection to places, digging out ancestral links, childhood memories, distant family stories, hoping to grow a base by narrative. Sometimes it works. Like it worked before in the APC. With Stevens adopting Tonko, facilitated by Kamara Taylor; and SI Koroma leaving the quicky cosmopolitan electoral sands of Freetown Central One for the more stable ancestral place of Maforki. But how successful are the present crew. Often, it feels forced, their attempt to connect to ancestral places. People can tell the difference between rootedness and recruitment.

Some have ethnic bases. Certain ethnic identities command loyalty across particular districts and deliver blocs of delegates almost structurally. That is political reality, whether we like it or not. It is not about prejudice; it is about social organisation. People vote where they feel culturally safe, and emotionally recognised.

Some have social-category bases. Strong followings among parliamentarians. Among youths. Among women’s groups. Among veterans. Rather than being accidental, these social bases are built over time through presence, advocacy, and reciprocal loyalty.

It is in these grounded spaces that many English speakers struggle. Their virtues may be loudly extolled within intellectual circles, but their bases often fail to consolidate. Praise does not automatically convert into delegates. Online admiration does not easily translate into ward-level arithmetic. You see strong applause in professional spaces, but weak anchoring in constituency structures.

And now a newer, more delicate base is entering the field: the money base. As the party moves to its important lower elections phase, we are seeing targeted spending in private. Spending on some party officials, at national level and down the structures, in the hope of pulling them into one’s column. News of cars given here and there. About the giving out of over-bloated “logistics” envelope there. It works on some. But it works unevenly.

Because this kind of base buys proximity, not necessarily conviction. It can shift behaviour in the short term. It can soften resistance. It can create temporary alliances. But it does not always create deep loyalty. Many recipients of such generosity understand the transaction clearly. They take what is offered, adjust posture, smile publicly, and continue calculating privately. So, while the money base can give a contender a strong push, it remains fragile if not tied to longer-term reciprocity. Without memory. Without shared struggle. Without embedded relationships. Without presence. Without trust. Money can open doors quickly. But it cannot always decide what happens once everyone is inside the room. Like all bases, it has limits. Money can mobilise attention quickly, but it does not always produce durable loyalty unless it is tied to something else.

But generally, people with bases are formidable in this contest. They already have starting capital many others are still trying to construct. However, they still need to expand. They still need to build bridges beyond their natural terrain. But they are not starting from zero. And in internal party arithmetic, that matters.

- The ‘We Bin Done Am Before People’

There is another advantage that matters deeply in internal party contests but is often under-theorised: tacit knowledge of internal elections.

This is not book sense. It is not even ordinary party sense. It is knowledge earned by having been inside the process; having run for party office, contested flagbearer elections, served as a running mate, or navigated both the old and new constitutional arrangements of the party. These are people who know where internal elections usually wobble. Where disputes emerge. Where counting becomes tense. Where rules are tested. Where misunderstandings turn into crises.

That knowledge matters.

Those who have contested party positions before, be it for national officers, flagbearers, or senior internal roles, carry with them an embodied understanding of timing, procedure, bottlenecks, and danger zones. They know what looks straightforward on paper but becomes complicated on the ground. They know where enthusiasm fades, where alliances fray, and where last-minute mishaps often occur. This kind of knowledge is not easily transferable. You have to live it.

Two of the current contenders ran for flagbearer elections under the new APC constitution and returned with respectable numbers. That experience gives them some baseline understanding of delegate behaviour, regional arithmetic, coalition limits, and institutional rhythm. They are not starting from imagination; they are building from memory.

Two others have also tested themselves in internal party elections for national officers, one successfully, the other unsuccessfully. But even the unsuccessful run confers knowledge. Losing teaches you different lessons than winning, sometimes sharper ones. It shows you where assumptions fail and where loyalty thins.

Then there are those who have been running mates in national elections. One was on a winning ticket and became Vice President, even though he lost his parliamentary contest in his district. The other ran on a ticket that did not win the presidency, but he himself has been successful in parliamentary elections and in internal party contests. These experiences matter differently, but they still matter. They expose candidates to national-level coordination, pressure, coalition management, and elite negotiation, skills that carry over into internal party struggles.

In short, these people know the game, though to varying degrees.

But knowing the game is not the same as being able to play it effectively.

Tacit knowledge only becomes power when it is operationalised. And that requires operatives. Some contenders know the terrain but lack the organisational muscle to act on that knowledge. They understand what needs to be done, but do not have the people to do it. Others have operatives but lack deep procedural understanding, relying instead on momentum or improvisation.

One particular contender stands out as having both: knowledge and operatives. He understands the internal process and has the machinery built over several internal party contests to implement that understanding. That combination is rare, and formidable.

There is also another figure who lacks deep internal experience but is rapidly assembling operatives through money. This raises a different question. How far can money-based operatives go? Can operatives recruited primarily through cash hold under pressure, confusion, or crisis? Will they stay aligned when money thins, or when loyalties are tested? That remains an open question.

Internal elections are not won by knowledge alone. They are not won by money alone. They are won when knowledge, operatives, timing, and trust converge.

- The EBK Whisperers

Another factor shaping the flagbearer contest is the question of the EBK endorsement.

Ernest Bai Koroma is not just a former president. He is a former party leader who still commands enormous symbolic and practical influence within the APC. His name carries weight across regions, structures, and generations of party members. For that reason, nearly every serious contender has sought his endorsement, some directly, others through proxies, and some by carefully allowing the impression that they have it.

One contender appears to have had an early advantage here. Over a year ago, the sense that EBK leaned in his direction gave that candidate an initial boost. In internal party politics, early signals matter. They shape perception, attract interest, and create momentum.

But that advantage did not remain uncontested.

Other contenders moved quickly to project similar claims, some explicit, others deliberately ambiguous. As more people began to suggest that they too had EBK’s ear, the original claim lost some of its sharpness. What initially looked like a clear signal became noisier. The endorsement, real or implied, began to diffuse. Its salience weakened as it was shared, contested, and quietly questioned.

This points to the double-edged nature of the EBK endorsement.

On the one hand, it confers legitimacy, reassurance, and access. It signals continuity. It comforts parts of the party that still locate authority and memory in his leadership. On the other hand, it attracts resistance. Over time, fractures have emerged around EBK himself. He has incurred the wrath of some formidable party actors who would actively resist his preferred candidate, precisely because they see his continued influence as overreach.

This is why many flagbearer contenders handle the endorsement delicately. They speak of it loudly among those who still listen to EBK, and quietly, or not at all, among those who bristle at his involvement. It becomes a careful political gymnastics of narrative: emphasised here, muted there, hinted at rather than declared.

The endorsement, then, is not a fixed asset. It must be managed. It can mobilise support in one space while provoking opposition in another. Those who rely on it too heavily risk being boxed in. Those who ignore it entirely risk alienating a significant constituency.

In this contest, the EBK endorsement functions less as a decisive instruction and more as a symbolic resource, useful, powerful, but volatile. Its value depends not just on whether it exists, but on where, how, and to whom it is invoked. And as the race tightens, that balancing act will become even more delicate.

Conclusions

The thing is there is touch of arrogance in anybody seeking to lord it over others as president of a country, be it democratically or dictatorially. Only those who seek to do it democratically often tend to hide the arrogance, some being better than others. Which is why someone, in fact, he’s amongst the flagbearer aspirants once advised me that you don’t insist on telling a person who is insistent on running for political office not to run. For the inherent arrogance often kicks in, and he makes you an enemy. Another thing: I know many amongst the flagbearers know what is required to win. But knowledge alone is not enough.

Winning an internal contest requires operatives, people who can move, persuade, reassure, and quietly rebuild bridges. Political knowledge needs boots on the ground. And boots on the ground do not appear automatically.

They are produced by reciprocity. Not general benevolence. Not moral appeal. But specific, remembered, mutual obligations. Who helped who. Who stood by who. Who opened which door when it mattered. Some of these ties have been hacked back over time – by conflict, by distance, by neglect, by shifting loyalties. But many are still strong.

So the question goes beyond whether contenders from the different categories have history or experience. Many do. The real question is whether they have assembled, or reassembled, the dense, forgiving, and strategic ground network required for a winning push.

What I often see instead are mismatched crowds. English speakers tend to assemble other English speakers. They sponsor English-speaking activities: the newspaper article, the radio programme, the panel discussion, the seminar, the dinner for this or that association. The populists gravitate toward Sallay-and-Ballay programmes. They spend big, or promise bigger, in those spaces. The party men move differently. They go to party occasions, formal party events, yes, but also informal party spaces: the businesses of party people, the regional structures, the district meetings, the constituency hangouts, the ward-level gatherings. They have been at this for a long time, accumulating amorphous social and political capital, slowly kneading it into something usable when the moment comes.

People count these things in these spaces.

And these spaces are significant. Conversations held in them enter the oral bloodstream of the party. Who spoke against who. Who defended who. What was said privately that later travelled publicly. Which hurts were repaired. Which hurts were gathered and stored. Where relevance accumulated. Where irrelevance began to show. In sickness, in health, and in death, networks are either strengthened or frayed.

This is where internal elections are truly fought.

Posters are great. I have seen many lately. They help build recognition. Grammar builds its own drama. They feed the evaluation machines of the book man dem en book ooman dem. But general recognition is not the same as party recognition, recognition from posters float in the air, recognitions from party activities, both formal and informal is more anchoring. And for many book man en ooman dem, their evaluation tricks are inherently demeaning of the overwhelming number of party voters, like if you don’t have grammar, you are only good enough for voting, or helping them reach out to some people.

In the end, the APC flagbearer race is not a grammar contest, a poster contest, or a generosity contest. It is a test of translation – who converts book sense into common speech, common sense into party sense, and party sense into organised votes. The categories we’ve traced – English speakers and their Verb Agreement Crowd, party machine people, populists, South-East contenders, people with bases, process veterans, and endorsement carriers are not verdicts but lenses. Most serious contenders carry more than one. But when the counting comes, it is not applause, buzzwords, or money alone that decides. It is reciprocity remembered, operatives deployed, presence felt, and networks trusted. That is the quiet arithmetic beneath the noise.